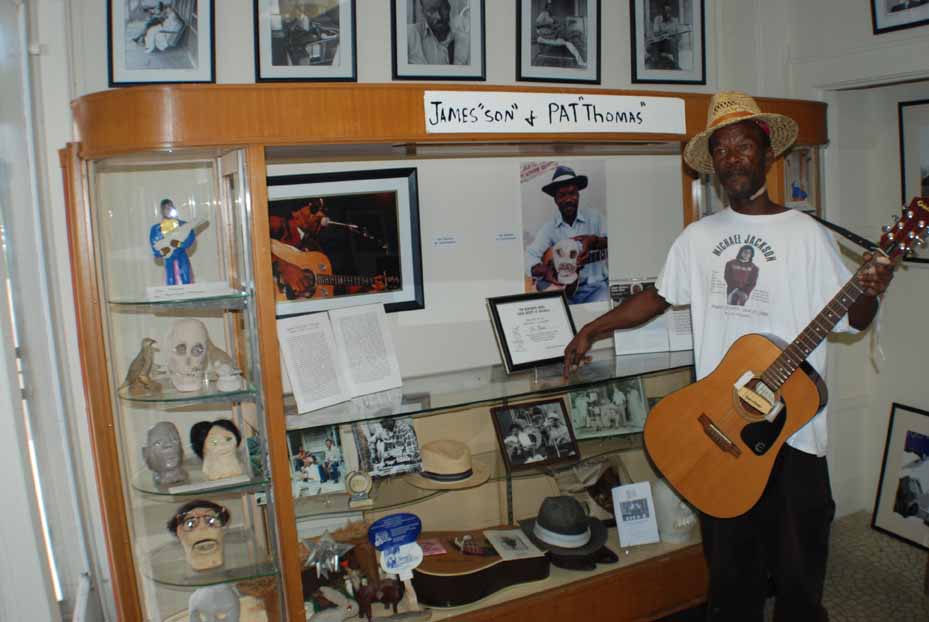

Blues guitarist and singer Pat Thomas is seen with a portrait of his father, bluesman James “Son” Thomas, in the Highway 61 Blues Museum in Leland, Mississippi.

Son of bluesman and folk artist James ‘Son’ Thomas carries on legacy and is leaving own mark in the Delta

By Albert C. Jones

America, The Diversity Place

HIGHWAY 61 BLUES MUSEUM — Here, in the Mississippi Delta, ubiquitous people perambulate in twelve-bar chord progressions. You know who they are, even without knowing their particular hardship stories. They are all flattened and gradually bent, Minor 3rd to Major 3rd. The most ardent of them, among other instrumentation, are bass line beat — foot tap or hand clap — while others trumpet or guitar slide, moan harmonicas with such force as to mimic sounds of a lonesome locomotive.

Blues people, especially sons and daughters, populate the Mississippi Delta. Their direct ancestors, patriarchs and matriarchs of the blues, are known for leaving here. Some left walking and some rode and some took flight. They carried with them twelve-bar chord progressions, the Minor 3rd to Major 3rd, to Memphis and then Chicago and then points all over the world. From them, ancestral subgenres were birthed and flourished as jazz, rhythm and blues, country, rock and roll and especially opera.

Their children have maintained covenants, repeated the first generation to the next, as faithfully as Abraham to Isaac, Isaac to Jacob and then to millions of the Children of Israel, especially the Prince of Egypt. Yes, there are princes and princesses born right here in the Mississippi Delta.

One of those princes is James “Son” Thomas. His son is Pat Thomas. Before the formal introduction, he is seen perambulating up North Broad Street here in Leland, which is among the many blues outposts in Mississippi. This morning he is wearing, against the morning warming, a dark-green wind-breaker, wide-brimmed straw hat, over a red bandana, black trousers, T-shirt that pays homage to Michael Jackson, brand new white sneakers as a cigarette dangles between pursed lips.

Inside the Highway 61 Blues Museum, Pat Thomas has taken a seat on a folding chair, giving a live performance for anyone who might show up. There is a fish bowl on the floor at his side. Tips are kindly appreciated.

Moments later, he sits for a recorded interview here inside the Highway 61 Blues Museum. When you Google Pat Thomas, many hits are found and he is to be considered Leland’s ambassador of the blues in full partnership with this museum. Father and son share a music exhibit here with their folk art creations. He is, perhaps, Leland’s most photographed and written about player of the Mississippi Delta Blues since the passing of his father.

James “Son” Thomas has a Blues Trail marker on Broad Street. James “Son” Thomas moved here from Yazoo City, Mississippi at age 35 and maintained Leland as home until his passing. Before he became a traveling man, Son Thomas worked as a porter in the Montgomery Hotel, which now houses the Highway 61 Blues Museum. He was born in Eden, Mississippi on October 14, 1926. He died June 26, 1993.

Pat Thomas speaks mainly as a narrator not to be interrupted. It is a style akin to a free-flowing monologue in a William Faulkner novel. This is what the son has to say about his father:

“My dad would always say, ‘Are you going to play?’ And I would say yes. And he would say, ‘Well, you better get your guitar because I’m going to start.’ He would put his hand on the guitar and play and you would sit and watch him and then try to play what he played.

“I got some of the ‘Catfish Blues’ off Mr. Eddie Cusic,” he says. “I admired every blues player for what they done. Willie Foster, Mr. Willie Foster, he played with my dad. My dad learned me most of it and the songs I play like ‘Rock Me’ and ‘Cairo Blues.’”

Guitar lessons also came from his Uncle Joe. Joe Cooper is known regionally for playing “Champs Elysées Blues” on electric guitar to vocals by Arthur Oneica, also known as “Poppa Neale.”

“My Uncle Joe, he was a blues singer also,” Thomas says with a voice one octave shy of full baritone. “He would come over sometimes and play my dad’s guitar. He showed me how to play some songs, but I learned most of it from my dad. My whole family, really, on my daddy’s side were kind of musicians. My Uncle Mitchell played saxophone in Chicago with a band.

“My father’s brother, his name was Mr. Al Perkins,” he says. “He lived in Detroit, Michigan. He had a recording studio. They don’t know who had him killed. Daddy went to his funeral. This happened back in the 1980s. Somebody came into the studio and killed him. They ended up giving everything to my daddy’s sister, Velma, but his wife got a lot of stuff, too.”

Though they are not married, as husband and wife, where princes and princesses are there has to be a reigning King of the Blues and reigning Queen of the Blues. His or her highness can reflect, as mentioned before, gospel, jazz, classical, rhythm and blues and opera. Truly, they are royals among royals.

Lineage works here because of proximity and legend. They grew, perhaps starting with one and then the twelve, Sons of the South, more poignantly princes of the Delta, Son House, Robert Johnson, Charlie Patton, Muddy Waters, Skip James, Bukka White, John Lee Hooker and the reigning king of them all, B.B. “Blues Boy” King.

Bessie Smith was the original Queen of the Blues. Koko Taylor took the mantel as Queen of the Blues in Chicago, meaning northern urban brick economy joined southern soil conditions as progenitor of the blues.

“When I got good enough to say I’m going out to play somewhere, my dad would take me up to Vicksburg,” Thomas says. “We went up to Vicksburg on a boat cruise. They had a big Fourth of July thing down in Jackson. We had to play at this football stadium. The fireworks went up and different bands played.

“Daddy and I came on later that night,” he recalls. “Daddy put that slide on and I was kind of like the bass man then. Oh man, we were rocking and everybody started standing up clapping and everything. We had our own hotel room. We stayed at the Sun N Sand Hotel in Jackson. Then we went to Oxford to the university there. In the studio there, they have the people sitting up high. But the performers were sitting low like and everybody else was sitting up high.

“That was back in 1985 or ’86,” Thomas says. “We went everywhere to Greenwood, Jackson, Vicksburg, Oxford, Cleveland and Clarksdale. We did these festivals up in Clarksdale every year before they moved the blues museum. The Clarksdale Blues Museum used to be in a library, but they moved it and put it back around behind the railroad tracks. Me and Daddy would go every year.”

There is one degree of separation of people who populate the Blues, like Son Thomas and Pat Thomas, as singers, musicians and people who have lived the blues. Once you know one within the progression you are harmonically connected to all and connected for all time. Is lineage the main reason why folks sing and play the blues anymore?

“It’s something that my dad brought to me,” Thomas says. “It’s something I want to carry on after him. Blues is a part of his life and I said I’m going to let it be a part of my life. I’m blessed anyway. Out of all 13 (Son’s children) of us, I am the only one who can pick the guitar. It makes me feel like a bluesman when I play because I have other people complimenting me and saying good things to me.

“It’s got to be something you want to do,” he says. “At first, I didn’t have the blues. By me complimenting myself, I said, ‘Hey, I got to do something here.’ I didn’t feel I was going to turn out as good as I have turned. Then things changed. I was depending on the guitar to do so much. It didn’t do what I thought it was going to do. After time went on, things started working out for me. I wanted to make money, going to different places playing the blues, communicating with the people and letting them know I am a bluesman.”

When people come to the Highway 61 Blues Museum, looking for a bluesman, if Pat Thomas is not in residence, then they are sent over to the “Black Dog” section of town to his apartment on Long Street. The Delta, of course, attracts people from all over the world who come in search of the blues.

While in Black Dog, people stop at Neisa Ray’s Restaurant for some baked chicken or poppy seed chicken, Ramen noodle salad, also what’s called a “Poor Man’s Éclair or that Sicilian meatloaf.

Thomas is a favorite subject of photographers because he looks are hard scrabble, his manners are homespun and he is the son of Son Thomas. Lineage aside, making it as a bluesman is not a given.

“It’s got to be something you want to do and you have got to have your mind on what you are doing,” Pat Thomas says. “At first it didn’t work, but now I have people come from all over seas just to give me an interview or just to get some of my artwork. That makes me feel like a bluesman. Right now, I have people from Germany and Japan, really. One lady wrote me a letter. They were here before. She wanted to talk to me, but her husband was in a hurry. They wrote me a letter saying they want to come back in April and talk with me.

“At first I didn’t really have the blues,” Thomas says. “I was singing the blues, but by me not feeling the blues on the inside, it made me not have the blues. When my dad passed, it made me feel like this is something that you will have to carry on for your father and yourself — make something out of yourself. I wasn’t good, good, good, but I knew some songs. I kept practicing and kept practicing.

“A guitar is something that you are going to have to play every day,” he says. “You are going to learn something every time you pick it up and hit a chord; you are going to learn something. If I put it down and haven’t played for a week or two weeks, then I have forgotten something. That’s just how it is, but if you practice every day on something, you going to learn you a new change, a new chord, and you are going to learn you a new song as you go.”

Blues, of course, are indigenous to this region because of conditions. If it wasn’t the blues, then it was the spirituals. Any moment of the day, it seems, can present the blues for which there is no off-season. The same is to be said about the spirituals. Power of that lament evokes cries from conditions, including up out of the soil that caused so many to hurt toiling in free labor and then victims of the sharecroppers’ ruses. The flight spelling the Great Migration had emigrants waving goodbye as they passed along the way station north.

Of the millions who left the South, there were those who stayed keeping the authenticity of place in the blues. This is what festival promoters had to say about Pat Thomas, the son, a former “Mississippi Delta Blues Society of Indianola Blues Artist of the Year.”

“Pat Thomas started playing while his father, the legendary James ‘Son’ Thomas, was here to teach him. Pat plays all his father’s songs and sounds remarkably like his dad. If you see a guy with a really big grin, you’ll know you’ve found Pat. Pat represented The Mississippi Delta Blues Society of Indianola, Mississippi in this year’s International Blues Competition in Memphis.”

For Pat Thomas everything musical is a gift, one generation to the next, from his father, James “Son” Thomas. Then the son began to write his own songs.

“I was like a bass man then, but later on, as time went on, I kind of learned songs on my own,” Thomas says. “One of the songs I had written is ‘The Way It Used to Be.’ Another song that I had written is called ‘The Woman I Loved Has Gone Away.’ She won’t be back no more. I’m begging you pretty baby before you walk out that door. When you come back this time, you know the feeling won’t be the same no more. But the woman I love has gone away.’

“It made me start singing more blues because people started enjoying me,” he says. “They would say, ‘Is this your song or your daddy’s.’ No, I would say. I had written that one. So when I cut my first CD, I had a lot of talk on it. They had some here in the museum, but they sold out. The people who did the recording on me, Broke and Hungry Records, they in Clarksdale, they furnished me 100 CDs and paid me $700 for doing the movie stuff and everything they did on me.

“They filmed me working in the clay and they finally gave me an interview like you and me are doing now,” Thomas says. “When I got ready to do the CD, they took me to pass Shelton (Mississippi), up to Bill Abraham’s house. We stayed there three days. The first day, I had just come back from Texas, and I couldn’t remember what I could sing. I really didn’t have it in my mind really what I could sing. I said, ‘Hey, I got to think here on what I’m going to do.’ I said, ‘Give me a minute, so I played this one song.

“Then the next day, they came and picked me up and I played other songs. I had just come back from Texas helping my sister move. Then on the third day, I played and played and he said, ‘You can’t think of nothing else?’ I said no. Then he said, ‘Well, I got more than I need.’ I think I did 13 or 14 songs.”

James Thomas was known as “Ford,” named after the models of trucks he made of clay while living in Yazoo City. The grandparents who raised him called him “Son.” First Lady Nancy Reagan once hosted a reception for James “Son” Thomas at the Corcoran Gallery.

His folk art — human skulls and birds fashioned from river-bottom clay — also toured galleries in other major cities. Some of his art is on display in the Highway 61 Blues Museum, including some snaggletooth skulls with glass eyes and hair. There are doves that were hand-shaped, smoothed with fine features, detail painted or splashed in white.

At 13 or 14 years old, Pat Thomas began an apprenticeship gathering river-bottom clay for his father, soaking the clay in water over night and mixing the workable clay with plaster of paris.

“I would take the clay and work it up for my dad,” Thomas says. “I do the art because I want to follow my dad. I can make birds to order and make some money. I make a bird and I can sell it for $10.”

He points to his father’s folk art on display in the museum.

“This skull you see right here,” Thomas says. “My father had two big art men (collectors). One was from Atlanta; the other was from Louisiana. The one from Atlanta, his name is Mr. Bill Arnett. The one from Louisiana, he is a dentist, Mr. Warren Lowe. He would send Daddy these denture teeth and daddy would use them in his skulls. Some of the teeth he used were human teeth.

“They both had art galleries,” he says. “They were big money guys. These guys spend two or three thousand dollars with my dad when they would come here. I spend a lot of time on the art. My dad taught me most the blues music and art.”

Pat Thomas’ folk art expresses cats and catheads marker drawings and birds made of clay. He has led the Lighthouse Arts & Heritage After-School Program at Delta State University. His dad’s art is part of the permanent collection of the Center for Southern Folklore in Memphis, the Center for Southern Culture at the University of Mississippi in Oxford; and of the Mississippi State Historical Museum in Jackson.

“Everybody liked my dad,” Pat Thomas says. “He was a nice person. He was just straight people. He wasn’t crooked and he tried to treat everybody right. That’s the way you should be.

“At first, I was a street thug,” he says. “After my father passed, I just got down really into the blues. I started playing every day. My brother, Wendell, he really didn’t give me my dad’s guitars and everything like he should have did. I know my daddy wanted me to have it. He let me have my father’s clothes and he let me have his rings and watches. But I give them to my sister, the one that come from up North.”

Memorabilia and folk art of bluesmen James “Son” Thomas and his son Pat Thomas are exhibited in the Highway 61 Blues Museum in Leland, Mississippi.